Cultivating solutions against climate change in Central America

Rural communities of the Central American Integration System (SICA) and FAO are confronting climate change with innovations that strengthen family farming, improve incomes, and protect nature.

21/04/2025

©FAO/Mario Araujo

In the countries of the Central American Integration System (SICA) lies the Dry Corridor, considered one of the most vulnerable ecoregions to climate variability and change. It is characterized by long periods of drought with rising temperatures or intense rainfall. People dependent on agriculture are the most affected socially, economically, and environmentally, with serious consequences for their food security and nutrition.

©FAO/Eduardo Calix

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) works with Central American governments to promote innovative solutions that support the work, leadership, and knowledge of women and men in preparing, alongside their rural communities, to face climate change, the degradation of natural resources, and limited access to technology and innovation — all key to achieving inclusive rural development, thus strengthening resilience and improving livelihoods.

©FAO/Katya Erazo

In Honduras, Pablo Osorto is a farmer from the community of El Castaño, in the municipality of Soledad, where, according to official data, about 78% of the population is engaged in agricultural activities. This locality faces daily threats from extreme weather events, resulting in crop losses and endangering food security for himself, his family, and his community.

©FAO/Katya Erazo

To address this situation, Don Pablo, as he is known in the community, contributes to developing of an innovative tool to reduce loss risks and optimize agricultural production: Agricultural Zoning for Climate Risk (ZARC). ZARC analyzes and maps agricultural areas based on their vulnerability to different climate risks. This initiative is promoted by FAO, the Brazilian Cooperation Agency (ABC), and the Government of Honduras.

©FAO/Katya Erazo

Through ZARC, Don Pablo collects essential data on his crops, from soil preparation to harvest, to determine the optimal dates for the next planting, assess success or loss probabilities, calculate water retention after rains, and better understand crop needs — contributing to better production in his community.

©FAO/Mario Araujo

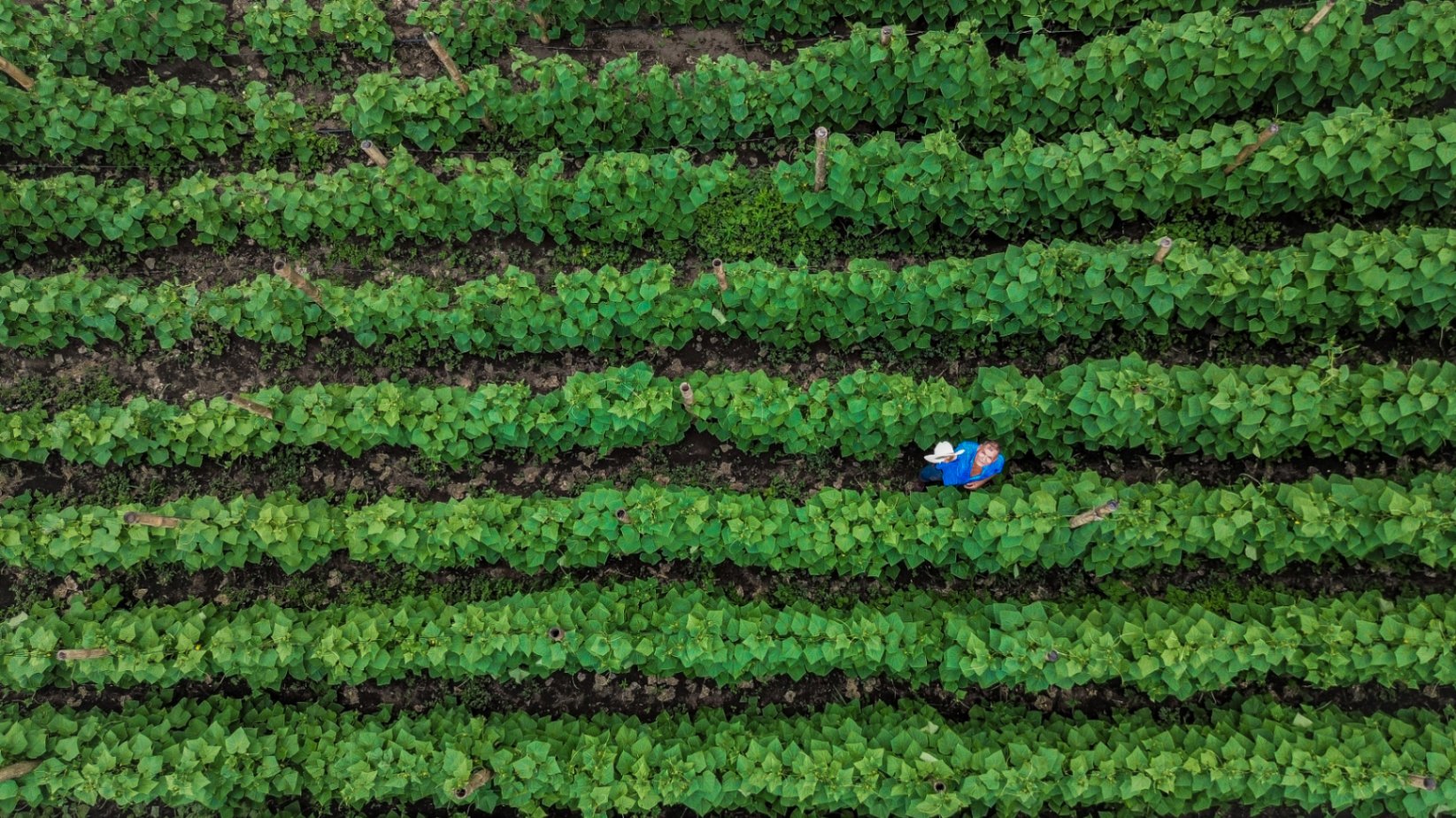

In El Salvador, 22-year-old Nubia Fuentes is a community promoter of a project implemented by FAO and financed by the Green Climate Fund (GCF) in Caserío La Peña, eastern region, aimed at proper soil management. Through Farmer Field Schools, she learned to use and maintain a drip irrigation system, allowing her to use water efficiently and diversify her production.

©FAO/Mario Araujo

Nubia is a young leader in her community who has inspired many women, who now apply what they have learned in their fields: conservation tillage and maintaining soil cover, building terraces and trenches to promote water infiltration, integrated soil fertility management to retain moisture, and agroforestry systems, among other climate-adapted practices.

©FAO/Rebeca León

In Costa Rica, Michael González is a soil research specialist at the Coffee Institute (ICAFE), passionate about understanding and strengthening the processes sustaining these essential ecosystems, which suffer degradation in 75% of Latin America's soils. In collaboration with FAO, the Global Soil Partnership, the Government, and the private sector, he focuses his work on organic fertilizers that enhance soil carbon storage capacity, thereby reducing greenhouse gas emissions and contributing to the fight against climate change.

©FAO/Valeria Navas

Through digital soil mapping, Michael and his team measure organic carbon content on farms in Costa Rica to develop statistical models linking environmental variables and soil properties. This facilitates land-use planning decisions, reduces soil degradation, and ensures sustainable agriculture.

©FAO/Valeria Navas

Michael’s work strengthens national research, innovation, and technology transfer institutes and goes beyond the lab. He teaches farmers good soil management practices in the field, since healthy soils are key to improving productivity, resilience, food security, and increasing farmers' incomes.

©FAO/Ingrid Saravia

In Panama, Adelina Sánchez is an indigenous leader from the Ngäbe-Buglé comarca. At 38, she is a single mother of seven and president of the Sustainable Artisan Agricultural Organization of Alto Cedro Women (OPAMU), dedicated to growing yam and yampi, which are highly demanded tubers in Panama. However, long distances to communicate with suppliers and potential buyers have limited their sales.

©FAO/Ingrid Saravia

Two years ago, OPAMU was selected to participate in a project seeking the digitalization of small-scale agriculture, implemented by FAO alongside the Government of Panama and other partners, with support from the People's Republic of China. They received training in digital tools and benefited from antenna and solar panel installations, creating a digital ecosystem that improves their market access and opens new opportunities.

©FAO/Ingrid Saravia

Adelina is forging new connections with suppliers and merchants, leading training sessions for other women farmers, and accesssing government information for the agricultural sector online — including phytosanitary disease alerts. These changes are revitalizing rural livelihoods, which were deeply impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

©FAO/Víctor Farfán

In Guatemala, Ingrid Ramírez is a 27-year-old farmer and leader living in the Cayur River micro-watershed in Chiquimula. Having been involved in her family’s agricultural work since childhood, she deeply understands the importance of protecting water as the cornerstone of agriculture and family sustenance around the micro-watershed.

©FAO/Víctor Farfán

To secure year-round water access and improve conservation, Ingrid and her family implemented a drip irrigation system and interconnected ponds to collect rainwater, along with other actions to reduce water waste, supported by FAO, the government, and funding from the Kingdom of Sweden. These efforts enable them to farm tilapia, irrigate their crops, and feed their animals.

©FAO/Víctor Farfán

These initiatives allowed Ingrid and her family to diversify production and establish the Maya Chortí Cooperative, which markets their products and those of other community members while participating in the School Feeding Program. Thus, they improve their household incomes and contribute to their community.

©FAO/Mario Araujo

The Hand-in-Hand Initiative, promoted by FAO alongside SICA institutions and other entities in the Dry Corridor, is generating effective responses to transition towards resilient territories in priority areas identified by the countries.